Marine service opened up new world for New Jersey attorney

Articles

Attorney Spotlight

View more from News & Articles or Primerus Weekly

By Brian Cox

As a teen, attorney Alex Keoskey knew he had more to offer the world than just a broad back and callused hands. What he needed was a path that might lead him beyond the blue-collar borders of Weehawken, New Jersey, into a world of broader opportunities. From what he could see, though, ways out seemed limited.

As a young lad, he would often spin a world globe and stop it with a jab of his finger and then imagine going to the country where his finger landed.

Located largely on the Hudson Palisades overlooking the Hudson River, Weehawken is connected to Midtown Manhattan via the Lincoln Tunnel. Now dramatically transformed through gentrification, Weehawken was a working-class town when Keoskey was growing up there. Most of the parents of his friends worked at the local Maxwell House Coffee factory in Hoboken or at the loading docks along the river. The waterfront, which is now all luxury condominiums with a stunning view of New York City, was then congested with freight trains traveling to and from the docks.

“It was a great place to grow up,” recalls Keoskey. “We were connected to New York City in so many ways. If we played hooky from school, we took the bus and in seven minutes we were in the center of the greatest city in the world.”

Despite being a voracious reader fascinated by history, geography, and politics, Keoskey was not the best student. He had few role models of academic achievement other than his teachers. No one in his family had completed high school, let alone gone to college. Most of the adults he knew chose to get a union job in the trades and raise a family. Higher education was rarely considered an option.

“I think I read every book in the library, but I didn’t want to sit in a classroom and take tests,” says Keoskey. “I probably had the worst grades in my class, but probably the best book knowledge of anyone.”

It’s evident to him now that his constant reading not only expanded his vocabulary and sharpened his writing skills, but it also developed a facility for absorbing information, which was likely one of the first seeds planted toward his later interest in becoming a lawyer.

When Keoskey was 16, he faced a critical life decision when his father suggested that he become his apprentice as a steel worker working in New York City. His father, whose right hand was like sandpaper from callouses and whose grip was crushingly strong, encouraged him to join his labor union. He would get good pay, vacation time, and a pension. Keoskey gave his father’s advice serious thought.

“That was a fork in the road for me,” he says. “I thought about that globe when I was a kid. I knew if I did what my dad was doing I’d never get out of New Jersey. Never see the world.”

Keoskey decided to go in a different direction. The next year, he decided not to finish high school and, instead, enlisted in the Marines.

“I looked as carefully as I could at how I could attain a better life,” says Keoskey. “The only way I could see from my vantage point was joining the military to get out of that physical environment, gain some discipline, learn some things, and travel.”

Keoskey says everyone was surprised by his decision, but after he explained his reasoning to his mother, she willingly signed the papers, allowing him to enlist at 17.

In basic training at Parris Island, he received invaluable advice from a drill sergeant who recognized the young recruit’s drive and potential. Keep your nose clean, he told Keoskey. Stay out of trouble and you’ll get promoted, you’ll get opportunities and choice assignments. Keoskey followed his advice and the drill instructor did not steer him wrong.

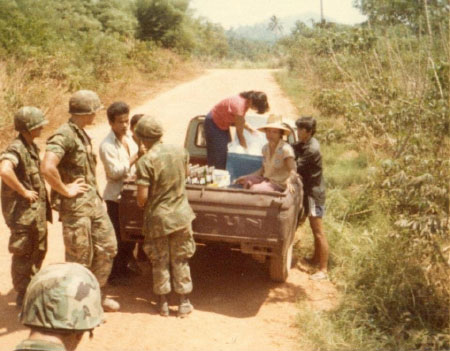

First stationed in Okinawa, Japan, with the 1st Marine infantry division, Keoskey went on to train in the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Thailand. Later, he was stationed with the 1st Marine infantry division in Southern California where he participated in desert training in the Mojave, mountain training in the Sierra Mountains, and an assignment for parachute training in Georgia. The entire time Keoskey says he thought he must be dreaming.

“All those places I would stop my finger on the globe and think I wish I could go there, I was there,” he says with a laugh.

In the course of earning the rank of sergeant and his paratrooper wings, Keoskey says he learned about discipline, teamwork, brotherhood, and the importance of collaboration – values and lessons that he has carried on into his legal career.

“One thing that is true anywhere you go is that taking orders is absolutely essential before you can give any orders,” he says. “Knowing what it’s like to be in the mud before you order people into the mud, that’s part of the military creed. I think it’s part of my civilian creed as well.”

When his four years were nearly up, Keoskey remembers picking up his uniform from the dry cleaners one day and thinking, “I really love wearing this uniform. Why should I get out?”

So he re-enlisted, choosing a position where he served alongside the U.S. Department of State in the USMC security forces for American embassies, which was a far cry from the jungle and cold weather training he had endured the past four years. Instead, he wore a crisp uniform with white gloves and sported a .357 Magnum revolver on his hip. He hobnobbed with diplomats at fancy events, with a diplomatic passport and top secret clearance.

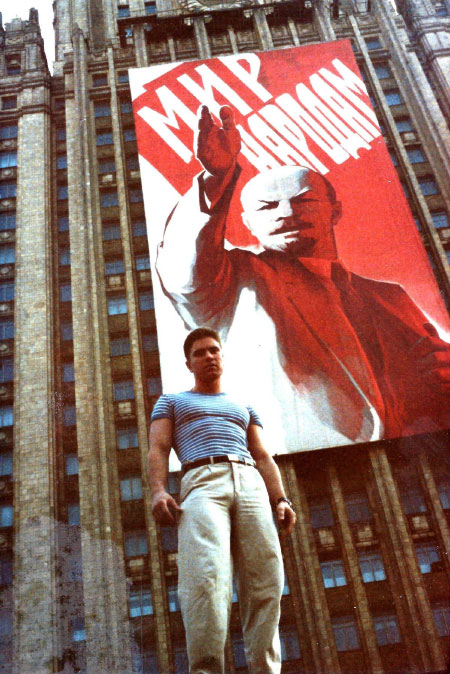

His first assignment was the American Embassy in Moscow. It was a unique time during the Cold War. During Keoskey’s three years stationed there, the Soviet Union went through three leaders: Yuri Andropov, Konstantin Chernyenko, and Mikhail Gorbachev. Keoskey occasionally accompanied couriers on their train trips to Helsinki, Finland and attending high level diplomatic events.

Keoskey describes the remarkable experience as similar to living in a goldfish bowl.

“You’re the only American military for thousands of miles around,” he says. “You have the KGB watching you. The people were wonderful, but it was a strange place to be.”

His time in Moscow helped to forge his political views.

“A government that has too much control over people’s lives is inherently dangerous,” he says.

After serving in Moscow, Keoskey was assigned to the embassy in Frankfurt, Germany, from where he was able in his off-time to travel around Europe. He was sent to attend several disarmament conferences, including one in Stockholm, Sweden.

The highlight of his embassy career, however, was his last assignment when in October 1986 he was detailed to be the senior Marine sergeant at the summit meeting between President Ronald Reagan and Gorbachev in Reykjavik, Iceland.

“The trust they had in me was a heady feeling,” says Keoskey, who had his old drill sergeant to thank for his advice. “I knew if I’d had even one mark on my record, I would never have gotten that assignment.”

When Keoskey’s second enlistment was up, he returned to New Jersey a changed man with a fundamentally altered perspective and far broader horizons. He enrolled at Rutgers University with a plan of pursuing a career in government.

As the first in his family to attend college, he describes walking onto the Rutgers campus as one of the scariest moments in his life – more frightening even than jumping out of a C-130 military transport aircraft. It wasn’t long, however, before he settled in and began eyeing law school.

He worked his way through college and law school as a bouncer at nightclubs such as the Palladium, the Tunnel and the Limelight in New York City. Working full-time and going to law school at night, Keoskey squeezed in study hours whenever he could.

Determined to be a litigator, he served for a year as a judicial clerk to Judge George Moser in the New Jersey Superior Court – Law Division, Hudson County, which proved to be valuable training ground for the court room.

Then, following advice that if he wanted to gain litigation experience, he should work for the government, Keoskey accepted an offer from the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office. The salary was low, but the hands-on experience was immense. His first three years with the AG were filled with tort litigation and trial work, defending state agencies against civil actions in state and federal court. His final three years, he was assigned to the Professional Boards Prosecution Section handling matters assigned by the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners with even more trial at the Office of Administrative Law.

The experience greatly shaped Keoskey’s current practice at Mandelbaum Barrett PC, which focuses on health care litigation and complex regulatory compliance issues for the firm’s healthcare and litigation groups. In addition to defending physicians, dentists, nurses and public and private health care entities in myriad employment, administrative and regulatory compliance challenges, he handles disciplinary actions brought by state licensing boards, investigations by various government agencies. He regularly litigates such matters in state and federal court, the New Jersey Office of Administrative Law and before hospital hearing committees.

Keoskey came to Mandelbaum Barrett in 2020, after 18 years with DeCotiis, FitzPatrick, Cole & Giblin, the firm he joined after leaving the AG’s office and where he parlayed his trial experience and his understanding of the health care regulatory system into a thriving client base.

At Mandelbaum, Keoskey has further expanded his client base and credits the firm’s focus on marketing and collaboration.

“It’s a great fit,” he says. “Something I always imagined a law firm to be.”

Keoskey and his wife Yana have three children. Their daughter Sophia is 16 and their son Aleksey is 10. Sadly, their second daughter, Alexandra, died from pneumonia in 2011.

He takes every opportunity to enjoy the outdoors. Nature calms him, he says, whether he’s hiking or landscaping.

And, of course, he still loves to read. His requirements for retirement are simple: An endless pot of coffee, a pile of books, and a view. A true budget retirement.

“It’s all I’ve ever wanted since I was a kid,” he says with a smile.