SF Regional Board attempts to clarify vapor intrusion approach

Business Law Articles

View more from News & Articles or Primerus Weekly

By Sherry E. Jackman and Brian E. Moskal

Greenberg Glusker

Los Angeles, California

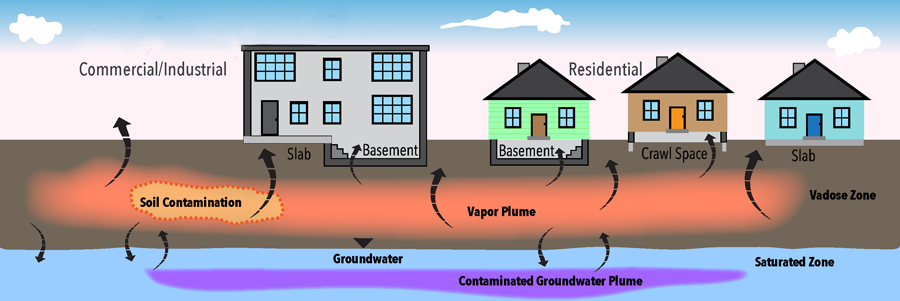

The San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board recently issued a fact sheet summarizing changes to its approach to remediating environmental impacts and mitigating vapor intrusion (VI) at properties impacted with volatile organic compounds (VOCs). This follows a January 2019 update to the Board’s vapor intrusion environmental screening levels—which are, not surprisingly, lower than ever before.

The email transmitting the fact sheet states that it is “intended to provide developers, cities, homeowners associations, and the public a summary of expectations for development at sites were VI may pose a threat.”

But managing expectations has always been a challenge for regulatory agencies and responsible parties at cleanup sites. Some have suggested that the agencies have regulated vapor intrusion “on the fly,” or by “underground regulations”—protocols that have not been formally adopted under the California Administrative Procedures Act.

Given this uncertainty, any written protocol detailing the Board’s present vapor intrusion approach can be helpful in providing clarity, even if that clarity may lead to increased costs for cleanup, monitoring, and redevelopment.

However, the fact sheet also raises several questions. One key question is whether other regional boards or oversight agencies such as DTSC will adopt the SF Board’s approach. Another question is whether this guidance will be incorporated into the statewide VI regulatory update that has been considered for some time.

Below are the key themes presented by the Board and thoughts on each:

Comment: Historically, sites could be closed if VIMS were implemented to address residual contamination. But under this principle, site closures will take more time and cost more money. It is unclear whether the Board is suggesting that VIMS can never be utilized as part of site closure. We’ve seen many successful VIMS incorporated into closures that adequately protect human health and the environment that are less costly and time-consuming than remediation of contaminants to target cleanup levels. It is unclear whether this strategy will be available in the future.

2.We prefer active depressurization systems for slab on grade buildings because they are more protective and allow for simpler monitoring.

Comment: Active depressurization systems are, of course, costlier to install and require more maintenance and monitoring than passive venting systems. Consistent with No. 1 above, this will increase the cost of site closures for slab-on-grade properties.

3. VIMS should be monitored for as long as they are needed to reduce the threat of vapor intrusion.

Comment: The Board and other agencies have not consistently required monitoring of VIMS. This new requirement, like those above, will result in increased costs analogous to those for groundwater monitoring. Those costs will need to be allocated in property transactions.

4. We need to review plans, construction completion reports, long term monitoring reports, and five year review reports.

Comment: Although the Board and other agencies have sometimes undertaken these reviews, it appears they will become more formalized and regimented. For example, consistent five-year reviews have not always taken place (except at properties overseen by USEPA under CERCLA), so this may require ongoing costs and allocation of those costs in property transactions.

5. A financial assurance mechanism is needed to make it clear that there are funds available to continue operation, maintenance, and monitoring for the lifetime of the system.

Comment: This requirement is analogous to financial assurance mechanisms for closure required for RCRA facilities. Although there are well-known financial assurance mechanisms in that context, this will also increase costs and require allocation in property transactions.

6. Developers should plan on allowing 60 days for us to review each report.

Comment: This timeframe may present one of the biggest challenges to redevelopment deals and other property transactions. Although the Board and other agencies are often overworked, resulting in delays in review of reports, some reports require more urgent processing because stakeholders are losing rent, productive use of land, their retirement assets, etc. So this timeframe may not be commercially reasonable in many cases. As we’ve known for the last decade, closure at a VI site can take a long time. On the other hand, this formalization of the review timeline may provide more certainty to stakeholders than open-ended timeframes.