transactions; (2) to permit the contin-

ued expansion of commercial practices

through custom, usage and agreement of

the parties; and (3) to make uniform the

law among the various jurisdictions.

the UCC's text or its purposes and poli-

cies, the UCC ordinarily supersedes the

statute. However, if the state statute was

specifically enacted to provide "addi-

tional protection to a class of individuals

engaging in transactions covered by the

UCC," a court may allow the state statute

to supersede the UCC.

should apply is a question of law.

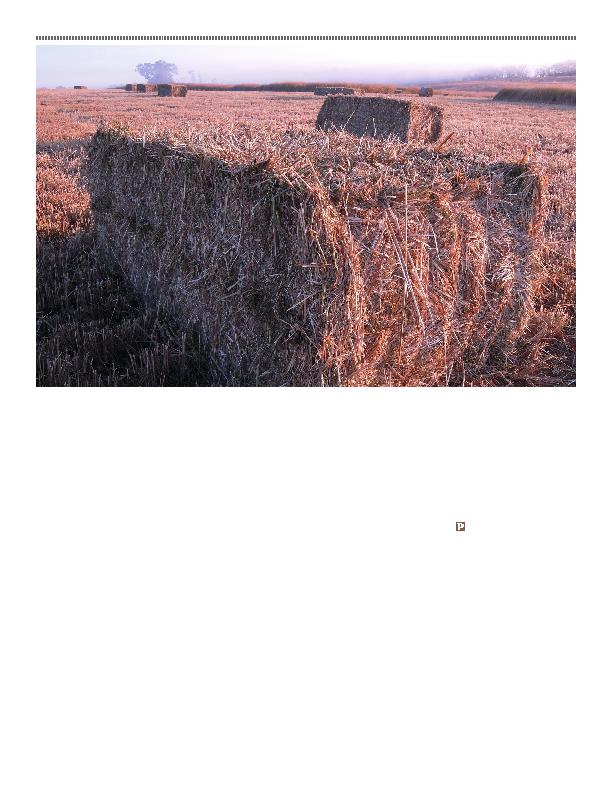

For example, a Tennessee statute

limits the duration of certain agricultural

contracts to three years.

pression to protect farmers. However, the

statute could be construed to be contrary

to the UCC's text, purposes and policies:

the UCC does not limit the duration of

contracts, and the limitations imposed

modern nor uniform with other jurisdic-

tions.

of a base farm income over a number of

years; the ability to amortize investment

in land, equipment or crop establish-

ment; some assurance that the contract

price would cover costs; and an opportu-

nity to develop expertise in the manage-

ment of a particular crop.

A state statute that limits the dura-

tion of agricultural contracts could be

problematic for the developing biomass

industry. A single season, or a two- or

three-year term, contract does not pro-

vide a biorefinery owner with feedstock

assurance. Because of the magnitude

of the investment, a biomass supply

contractor will likely seek to contract for

a significant percentage of the facility's

biomass feedstock requirements during

the development phase of the facility. A

three-year contract term, even with the

possibility for renewal, is probably not

sufficient. Balancing of the various laws

supply is an important consideration.

The discussion of appropriate terms

to include when contracting for biomass

is one that must be continued among

farmers, feedstock suppliers, bankers

and biomass conversion facility owners

as the industry progresses, to eventually

find a middle ground on which all parties

can agree.

production, a precise schedule for the use of acceptable

inputs, and specific production practices to be used by

the farmer.

etc.

(1995).

5 Production Contracts, http://www.farmfoundation.org/

(last visited Oct. 18, 2012).

7 U.C.C. § 1-103(a) (2004).

8 U.C.C. § 1-103, cmt. 3 (2004).

9 Tenn. Code Ann. §43-15-101 (2012).

10 The Tennessee statute was enacted in 1932 and has

other state has a similar statute limiting the duration of

agricultural contracts.